Current News

- 09/27/201610/28/2016

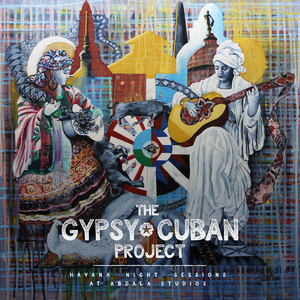

La Casa Gitana: How the Romani Virtuosi and Cuban Greats of the Gypsy Cuban Project Bonded on Sultry Havana Nights

Earlier this summer, fifteen Romani musicians boarded a flight from Paris to Havana. Awaiting them were dozens of Cuban musicians itching to jam with the Gypsies, wondering how, or even if, their musical roots would blend.

Driving this giant experiment was Damian Draghici, a Romanian musician and political activist of Roma heritage obsessed with the island’s striking, vibrant music. He assembled top players from across Central and Eastern Europe. He tapped Cuban greats like Omara...

- Latin Jazz Network, Article, 03/17/2017, The Gypsy-Cuban Project: Damian Draghici Text

- Latin Dance Community, Album review, 11/28/2016, NEW TROPICAL MUSIC RELEASES – NOVEMBER 2016 Text

News

Earlier this summer, fifteen Romani musicians boarded a flight from Paris to Havana. Awaiting them were dozens of Cuban musicians itching to jam with the Gypsies, wondering how, or even if, their musical roots would blend.

Driving this giant experiment was Damian Draghici, a Romanian musician and political activist of Roma heritage obsessed with the island’s striking, vibrant music. He assembled top players from across Central and Eastern Europe. He tapped Cuban greats like Omara Portuondo (best known for her role in the Buena Vista Social Club). Then he urged them to make music together.

A few weeks of late-night recordings, backyard jams, and pop-up performances in the streets of Santiago and Havana, and Draghici knew they were on to something. The final result, The Gypsy Cuban Project’s Havana Nights (Universal Romania; release: October 28, 2016), packs swinging rumbas with galloping accordion, and brilliant salsa numbers with flourishing Gypsy brass and fiddle, all recorded in Havana.

Behind the musical chemistry lies a history of enslavement, migration, and escape that forges unexpected bonds between two seemingly far-flung cultures. “There is a Latin feel in some Gypsy music,” reflects Draghici. “There’s a lot freedom in the groove. There’s a lot of passion in the singing. There was a connection in the end, and lots of sharing.”

{full story below}

Draghici is a force to be reckoned with: Along with a busy music career, he has served the citizens of Romania as a senator, or more recently, as a member of the European Parliament. He has also nurtured a decades-long passion for Cuban music.

After digging into his own ancestry, he discovered a surprising Cuban connection: One of his relatives on his mother’s side, like approximately 90,000 other Romani, had traveled to Cuba to escape Germany in early 1940s. Most moved on immediately after the Revolution. These weren’t the first Roma on the island, as Romany, themselves enslaved, were used as manual labor on slave ships bringing Africans to the new world.

The upheaval and sorrow of servitude aren’t the only things that connect the two sonic worlds, however. They share some basic attitudes and specific approaches to making music. Draghici thought he could make that connection work. “Both Romani and Cuban people share such an intense passion for music. They both dance, sing with such passion about love and pain, not to mention the talent among each cultures’ musicians, I thought it would sound cool,” says Draghici.

Cool, indeed, in theory. But what would this kind of collaboration actually sound like? Draghici didn’t know--and that didn’t stop him. “Everybody we spoke to in Romania and in Europe wondered, ‘How is it going to sound?’ Cubans asked the same thing. I said, ‘I have no idea,’ so we had to go there to find out.”

At first, it didn’t click. Throughout the first week of collaboration in Cuba, Draghici and the director of the project weren’t happy with what they were hearing. Initially, the two schools of music felt so rhythmically distant, but they found ways to connect anyway.

They took up in a rented bayside house in Havana that the locals began calling “La Casa Gitana” or “The Gypsy House.” They’d host parties and jam together. They roamed the city with their instruments, in true Gypsy fashion, playing in backyards and in the street.

Then, one night, Draghici finally got his answer. A bunch of musicians, both Romani and Cuban, showed up at a bar in Havana called El Flauto Magico. The epiphany came with a Gypsy tune, “Djelem, Djelem.” The famous song became mournful, dramatic, and processional like a slow march, while at the same time, danceable, joyous, and jazzy. It struck a perfect balance between the two groups’ sounds.

“I knew that was the sound. It was like flipping a switch, the light came on,” said Draghici. “We just needed a dozen more successful songs for an album.”

Slowly, after hours of rehearsing, arguing, and testing countless songs together, they’d stumble upon a song that would bond the musicians. “You’d see it on their faces,” said Draghici. Then they’d move on to the next and the next and the next, when suddenly they realized they had not come together for nothing. They knew they would have an album.

So many tracks on the album could easily pack a dance floor, like “Hopai Diri Da Recall,” an enthusiastically adapted Gypsy tune with a powerful gang of bilingual vocals, danceable Latin percussion, bursting brass, and shredding clarinet. Meanwhile slow and passionate tracks like “Jungali” burn with dramatic violin by Marin Alexandru and shared lead vocals by Haila Mompie and Panseluta Feraru.

“It became easy for the Roma musicians to get the Latin melodies and similarly easy for the Cubans to adapt the Gypsy tunes,” said Draghici. “You could see they were clearly happy together.”